Квантовый хаос

Переведено 11.11.05 с оригинала: ScienceDaily.com.

|

Researchers Demonstrate Quantum Chaos During Atom

Ionisation For The First Time Max

Planck Institute of Quantum Optics. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics, investigating the chaotic behaviour of the quantum world, have been able to give

the first ever demonstration of quantum chaos during atom ionisation.

Using laser light, they released electrons from rubidium in a strong

electromagnetic field. The researchers measured typical fluctuations in the

electron current, which is subject to the frequency of the laser light, and

which arose from the chaotic movement of the electrons. The experiment is

based on an experiment from the early days of quantum mechanics demonstrating

the photoelectric effect. (Physical Review Letters, In

the macroscopic world of everyday life we often have 'deterministic chaos'.

Events like weather and ocean currents, the movement of heavenly bodies, or

the growth of insect populations can all be

described in exact formulas. They are indeed 'deterministic'. But the way

they proceed in reality is highly sensitive to initial

values. Even the smallest failure to measure the initial conditions can make

a long-term prediction impossible. Physicists call such systems 'chaotic'. Microscopic processes can

also be very complex. Quantum mechanics rules out the idea that the world of

atoms has 'deterministic chaos'. Among other reason for this, quantum

mechanical systems develop non-deterministically from many simultaneous

initial states. In quantum chaos research

physicists are looking for similarities, in the quantum world, to the

deterministic chaos of the everyday world. In this way, scientists at the Max

Planck Institute of Quantum Optics have been investigating chaos in quantum

mechanical systems that would be deterministically chaotic according to the

rules of macroscopic physics. Scientists working with Gernot Stania and Herbert

Walther have now succeeded in finding the first experimental evidence of

quantum chaos in a system in which the components, during the experiment, in

principle can disperse in any direction. They harked back to an historical

experiment: demonstrating the photoelectric effect by releasing electrons

onto metal when light is projected on them. In the classical

experiment, electric voltage is created across two metal plates, one of them

covered with an alkali metal. The experimenter hits the alkali metal with

light at a particular frequency (and thus energy).

As soon as the energy moves above a certain amount, the light frees the

electrons from the metal, which is observable as electric current. Albert Einstein

published his explanation for this effect a hundred years ago, which was

important for the development of quantum theory and

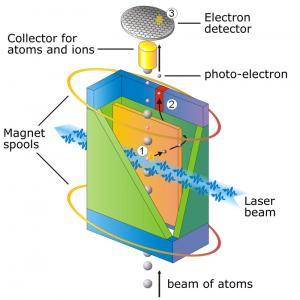

recognised with a Nobel Prize in 1921. The scientists from the

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics adapted the classical experiment to

their needs. In the modern version, the alkali metal is not applied to a

metal plate, but is replaced in the experimental setup by a flying beam of

rubidium atoms (compare with image 1). The atoms are then exposed to both an

electrical field and a strong magnetic field. As in the historical

experiment, the atoms are only hit with a light of a particular frequency

which is able to cause them to release electrons. This electron beam is

measured subject to the light frequency.

Between the magnetic

field, the electric field, and the electrostatic forces in the atom (the

attraction of protons and electrons), three different forces are acting on

the electrons in the rubidium atoms, each of which provokes very different

electron movements. As long as one of these forces outweighs the others, the

movement of the electrons is simple and not chaotic. That is the case, for

example, when the electron has not yet absorbed laser light and finds itself

near the atomic nucleus. However, in the moment in which the electron takes

up a light particle, it changes to a high energy state and thus falls more

under the influence of the external electromagnetic field. Its movement then

becomes chaotic. In the process of this movement, the electron moves farther

and farther from the nucleus, until it is free. The chaos in the movement

is demonstrated through the fact that the electron beam fluctuates in a

particular way which matches the energy of the light particles. These

fluctuations are called 'Ericson fluctuations'. The

researchers were not only able to demonstrate the Ericson

fluctuations, they were also able to adjust the

initial state of the strength of the electric and magnetic field, and thus

how chaotically the system behaved, according to the rules of macroscopic

physics. In this way, they were able to show the connection between

deterministic chaos and the fluctuations of the photocurrent. The more

chaotically the system reacted, according to the rules of macroscopic

physics, the stronger the measured fluctuations. The original news

release can be found here. |

Исследователи

впервые демонстрируют квантовый хаос при ионизации атома Институт Квантовой Оптики им.Макса Планка. Ученые из Института Квантовой Оптики им.Макса Планка, исследующие хаотическое поведение квантового мира, поставили эксперимент, демонстрирующий квантовый хаос при ионизации атома. Используя лазерный луч, они заставили рубидий испускать электроны в сильное электромагнитное поле. Исследователи измерили типичные колебания в электронном потоке, образованные в результате наложения частоты лазерного излучения на хаотическое движение электронов. Эксперимент основан на классическом эксперименте, демонстрировавшем фотоэлектрический эффект. В макроскопическом мире каждодневной жизни мы часто наблюдаем детерминированный хаос. События, подобные атмосферным и океанским потокам, движение небесных тел, рост популяций насекомых можно описать точными формулами. Они действительно ' детерминированы '. Но путь, по которому подобные системы переходят из одного состояния в другое, слишком чувствителен к начальным условиям и параметрам среды и не поддается детерминированному описанию. Даже самая маленькая ошибка в измерении начальных условий может делать долгосрочное предсказание невозможным. Физики называют такие системы ' хаотическими '. Микроскопические процессы также могут быть очень сложны. Квантовой механикой управляет идея о том, что миром атомов управляет детерминированный хаос. Физики-ядерщики ищут подобия между квантовым миром и детерминированным хаосом макромира. Ученые из Института Квантовой Оптики им.Макса Планка исследовали хаос в квантовых механических системах, которые можно определить как хаотические в смысле макроскопической физики. Исследователи, работающие вместе с Gernot Stania и Herbert'ом Walther'ом, получили первое экспериментальное свидетельство квантового хаоса в системе, в которой компоненты в течение эксперимента, в принципе, могут рассеиваться в любом направлении. Они основывались на классическом эксперименте демонстрации фотоэлектрического эффекта, заключающегося в испускнии металлом электронов под воздействием света. В классическом эксперименте электрическое напряжение создано между двух металлических пластин, одна из которых покрыта щелочным металлом. Экспериментатор облучает эту пластину светом определенной частоты. Как только энергия света превышает некоторый квантовый уровень, электроны отделяются от металла, образуя электрический ток. Альберт Эйнштейн дал объяснение этого эффекта сто лет назад, что было важно для развития квантовой теории и отмечено Нобелевской Премией в 1921. Ученые из Института Квантовой Оптики видоизменили классический эксперимент. В современной версии щелочной металл не применяется, его заменили в экспериментальной установке лучом из атомов рубидия. Атомы были подвергнуты воздействию как электрического, так и магнитного полей. Как и в историческом эксперименте, атомы облучаются светом определенной частоты, способной заставить их испускать электроны. Этот электронный луч измеряется по мере изменения частоты света. Три различных силы действуют на электроны в атомах рубидия, каждая из которых вызывает совершенно различные движения электрона. Это магнитное поле, электрическое поле и электростатические силы в атоме (силы притяжения между протонами и электронами) . Пока одна из этих сил перевешивает другие, движение электронов - простые и не хаотические. Это имеет место, например, когда электрон еще не попал под лазерное облучение и находится около атомного ядра. Однако, в тот момент, когда электрон сталкивается с легкой частицей, он переходит на более высокий энергетический уровень и сильнее реагирует на внешнее электромагнитное поле. Его движение становится хаотическим. В процессе этого движения электрон переходит на все более удаленные от ядра квантовые уровни, пока не становится свободным. Хаос в движении демонстрируется тем фактом, что электронный луч колеблется специфическим способом, который соответствует энергии легких частиц. Эти колебания называются эриксоновскими колебаниями. Исследователи смогли не только продемонстрировать эриксоновские колебания, они смогли также отрегулировать начальное состояние сил электрического и магнитного полей таким образом, что хаотичное поведение соответствовало правилам макроскопической физики. Таким образом, удалось показать связь между детерминированным хаосом и колебаниями фотопотока. Источник: ScienceDaily.com. |